Today, I'm a wifi parasite in the uSwitch office. Over lunch, Tom Hall pointed out that nilenso doesn't pay bonuses, instead opting for transparent salaries, chosen on merit to the degree possible. (Read more on our original post: "Huh? A Software Co-operative?") His question is one we get often: How do we decide salaries?

Our first stab at this was a model we'd inherited from other companies we'd worked at: have salary bands which match up to the skill and experience of the current staff, match that to the available cash, and set salaries accordingly. At first, we actually started off with an approach that was even more naive -- rather than salary bands, we had "levels". To improve one's salary beyond the usual bump provided for inflation, it was really a huge leap from "college kid" to "junior" to "intermediate" to "senior". Under this model, we also had no real vision for future "levels" (yagni?); the most senior person on staff was the highest salary we imagined paying.

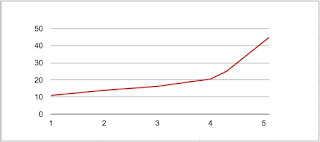

This system is very obviously broken when graphed this way, but there are a number of other little firms in Bangalore which still operate this way. The inevitable conclusion is the introduction of "Level 2.5" and other confused ideas which make a broken system even worse.

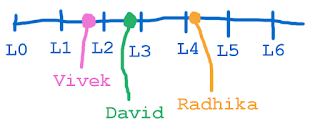

Incrementing on this inherited model, we tried to smooth out the curve and divide up each "level" into ten increments. The old integer levels (now L1.0, L2.0, and so on) represented concrete, documented responsibility changes under the incremental system. The new incremental levels (L2.2, L4.3) were sort of tweened into thirds. A concrete example: L2.0 is a intermediate developer who is capable of driving design decisions (and a pair, if pair programming). L3.0 is an intermediate developer who can mentor, architect individual systems, and drive hiring decisions. L2.1 to 2.3, L2.4 to 2.6, and L2.7 to 2.9 give us three junior-to-senior tiers to play with when describing the growth of a developer from a "solid intermediate pair" to "mentor". With increments, everyone grew 0.2 or 0.3 each year, rather than jumping from L2 to L3 every three years. (In practice, the integer system usually meant redesigning the entire system every year.)

Once we'd finished the review cycle, we took a step back and tried to answer the "what does the future look like?" question. Working with "explicit is better than implicit" as a foundational rule, one is forced to visualize a complete salary framework. This implies a couple of things:

1) "complete" inherently means "global"

2) "complete" inherently means "lifelong"

Therefore, our salary bands had to map a curve from the lowest-paid, straight-out-of-college hacker to the most talented and experienced computer scientist money can hire. The former is easy enough to imagine... we've all hired dozens of those folks. But the best of the best, the world over, near the end of her career? I'm not even sure I've met such a person.

There's huge value in imagining the highest salary you will ever pay. We humans don't like to spend a lot of time pondering the end of our productive days. We like to spend time pondering the scary last chapter of our mortality even less. But these things are real. Everything real, everything fact-based, has to be laid bare in a completely transparent organization.

Our first pass was difficult, uncomfortable, and (of course) incorrect.

Fast forward one year to nilenso's 2015 review cycle, and it was apparent our 2014 curve didn't really fit. We'd made a few mistakes: high-end salaries (L4.x and L5.x) were too high, some jumps had been too big, the L1 salary band didn't fit on a smooth curve. (You can see this from the graph: the L1-L2 salary band has a steeper slope than L2-L3 and the inflection at L4-L5 is also obviously incorrect.) However, being completely honest about the data is only step #1. Step #2 is to be completely honest with _ourselves_: we'd made some mistakes in 2014 and we needed to correct them. We jiggled the L1 salary band a bit, some L2.x salaries didn't jump as much as expected, L4.x and L5.x salaries came way down.

Our second pass was difficult, uncomfortable, and (will likely be) incorrect.

...but it was a little less difficult, a little less uncomfortable, and (hopefully) a little less incorrect. The goal is not perfection. Next year, the benefit of hindsight will expose this year's mistakes and we can once again go through the mild discomfort of correcting them. And, with any luck, our second pass was enough of an improvement on our first that the mistakes will be smaller.

I've jumped ahead of myself a bit, here. The 2015 salary curve starts at about 7.5 lakh rupees ($12,000 USD) for Developer Level 0.0 and curves relatively smoothly up to 317 lakh rupees ($500,000 USD) for our realistic Developer Level 10.0. Everyone at nilenso is presently L1.x - L4.x, so don't get too excited about multi-crore salaries we might lavish you with. But how did we arrive at the curve?

First, Tim (being Tim) spent a Saturday automating the review workflow. The nilenso reviews app was born. Since any annual review cycle for any company tends to be little more than swimlanes of todo lists, it was the perfect job for Rails and Heroku. Tim, and anyone else at nilenso, could modify the workflow, relationships, and privacy across the reviews process in a matter of minutes with a quick code change and redeploy. Everyone could glance at https://reviews.nilenso.com to see their feedback and to hassle people who hadn't reviewed their colleagues yet.

The review app lets everyone ask for reviews/feedback from specific people. Reviewers are then tasked with completing a review for everyone who asked them. Each review is a free-form text entry field and a "suggested level" field, if the reviewer is comfortable suggesting the reviewee's growth in the past year. Though we'd initially planned on discussing salaries directly, the Level system addresses skill, contribution, network, and experience rather than what anyone "feels" other employees should make. This has the immeasurable advantage of keeping emotion out of the equation and keeping everyone focused on the facts at hand.

Second, Deepa facilitated the review meetings. After scheduling and planning each meeting with Tim, she played the role of non-participating facilitator to discussions which included the reviewee, everyone who gave them a review in the app, and anyone else who wanted to listen in. Each meeting started with everyone in the room grabbing a laptop (or iPad) and quickly re-reading the reviews in question, to make sure they hadn't missed anything. Then the reviewee would summarize their self-review and the reviews they'd received from their coworkers; we did away with "sponsors" and let the person speak for themselves. At the end of the summary, s/he would explain whether the average Suggested Level (calculated by the app) seemed appropriate. The floor was then open to discuss and debate. By the end of these meetings, everyone knew what everyone else's level would be for the upcoming year.

The meetings cost us a lot of time but everyone agreed it was time well spent. Attempts to limit participation in 2014 hadn't prevented the review meetings from cutting into everyone's work day, and in 2015 there was no question that the open forum felt totally transparent.

A good rule of thumb for corporate transparency: You're probably doing it right when everyone finds the transparency boring.

A small consulting company has a fixed amount of money to spend on annual raises. By working through the entire review process without discussing money, we were free to be completely honest with one another with feedback^ and conversation. Certainly some conversations were harder than others but the overall process was smooth. Once everyone's reviews were complete, Deepa took away a Level Curve (really more of a straight line with dots on it, like above) which she could retrofit our earnings onto. That became the proposed Salary Curve, which we discussed one last time and then finalized.

^ It's worth noting that we expect feedback to be a continuous, daily process. If someone is giving you new constructive criticism for the first time only in the annual review process, they've failed you miserably. Since peer-to-peer reviews take the form of "feedback" the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. Though we may muddle terminology, we try not to muddle intent.

A meaningful salary curve for operations staff is even murkier. Though we have 3 people who do operations (security & operations, cleaning, operations & basic accounting) and their salaries are similar, the industry average for these positions is unfairly low in India. We're also less sure what the growth path for each of these folks will be in the coming 2 or 3 years. Mintu will certainly get bored of working security at some point, and we need to make sure the Salary/Level Curve for Operations makes sense in light of that.

Though nilenso has a very liberal paid leaves policy (unlimited sick leave and plenty of vacation), we do not have sabbaticals (unpaid leave) figured out. Sabbaticals present a number of difficulties: Does a senior employee have more access to sabbaticals than a junior employee? Someone senior undoubtedly makes more money and has longer vacations in any company, but most companies don't offer sabbaticals. Is one's salary based on a 12-month working year, or 12 months less any sabbatical months? How can we plan sabbaticals far enough in advance that they're comfortable for both us and our clients? How many sabbaticals can a consulting firm support in one year? At one time?

Nilenso has expenses. An office, non-billable staff, food, travel, books/classes/conferences, and a couple of internet connections. While everyone would love to take a sabbatical whenever they like, it is damaging to a company if the company isn't 100% remote and overhead-free.

Tom hasn't chosen a model yet, and I'm guessing it will evolve with his co-op. His key issue is the ability for employees to take sabbaticals (he describes the need for sabbaticals as a "founding principle"), which for a consultancy implies salaries will swell and shrink with billable hours. At nilenso, we've had varying success with mixing hourly billing rates and monthly retainers. Depending on one's billing model, the process of taking sabbaticals could shift. Once Tom's co-op Gets Huge(tm), it will require operations, admin, and accounting staff. Those folks still need to get paid even if all the developers are off at HillHacks for a month, so I'm excited to see what solution he and his team opt for.

We will keep publishing our experiments, failures, and learnings. And we'd love to hear from you at hello@nilenso.com if you have a suggestion!

Huge thanks to Tim and Deepa for making this post happen!

Our first stab at this was a model we'd inherited from other companies we'd worked at: have salary bands which match up to the skill and experience of the current staff, match that to the available cash, and set salaries accordingly. At first, we actually started off with an approach that was even more naive -- rather than salary bands, we had "levels". To improve one's salary beyond the usual bump provided for inflation, it was really a huge leap from "college kid" to "junior" to "intermediate" to "senior". Under this model, we also had no real vision for future "levels" (yagni?); the most senior person on staff was the highest salary we imagined paying.

This system is very obviously broken when graphed this way, but there are a number of other little firms in Bangalore which still operate this way. The inevitable conclusion is the introduction of "Level 2.5" and other confused ideas which make a broken system even worse.

Incrementing on this inherited model, we tried to smooth out the curve and divide up each "level" into ten increments. The old integer levels (now L1.0, L2.0, and so on) represented concrete, documented responsibility changes under the incremental system. The new incremental levels (L2.2, L4.3) were sort of tweened into thirds. A concrete example: L2.0 is a intermediate developer who is capable of driving design decisions (and a pair, if pair programming). L3.0 is an intermediate developer who can mentor, architect individual systems, and drive hiring decisions. L2.1 to 2.3, L2.4 to 2.6, and L2.7 to 2.9 give us three junior-to-senior tiers to play with when describing the growth of a developer from a "solid intermediate pair" to "mentor". With increments, everyone grew 0.2 or 0.3 each year, rather than jumping from L2 to L3 every three years. (In practice, the integer system usually meant redesigning the entire system every year.)

Reviews in 2014

Once we had the incremental model in place, we tried to iterate on our previous experience of "behind closed doors" reviews, as well. The goals were transparency, fairness, and comfort. Big all-hands referendums could be embarrassing -- and had proven inefficient for all sorts of other decisions, which caused us to elect a small "Executive" (two people), similar to an elected Board of Directors in a large corporate co-operative. The Executive drove the review process. We kept track of each review on a whiteboard, so everyone could see what was going on as it happened. Each review included the two people from the Executive, the person being reviewed, that person's "sponsor" (another vestige of another company we'd worked for - namely, ThoughtWorks), and their closest coworkers/team members. The sponsor presented a proposed salary, and the review discussion worked backward from there. The process worked reasonably well, but as we discovered this year, we were a bit too liberal with salary jumps.Once we'd finished the review cycle, we took a step back and tried to answer the "what does the future look like?" question. Working with "explicit is better than implicit" as a foundational rule, one is forced to visualize a complete salary framework. This implies a couple of things:

1) "complete" inherently means "global"

2) "complete" inherently means "lifelong"

Therefore, our salary bands had to map a curve from the lowest-paid, straight-out-of-college hacker to the most talented and experienced computer scientist money can hire. The former is easy enough to imagine... we've all hired dozens of those folks. But the best of the best, the world over, near the end of her career? I'm not even sure I've met such a person.

The COMPLETE Salary Curve

So, for the sake of argument, let's assume we're hiring Leslie Lamport, assuming he makes a high salary at Microsoft Research. Or perhaps a senior-most computer programmer from Google. A little asking around, Glassdoor, and that infamous secret.ly "salaries at Google" thread all told us that our ballpark figure of $500,000 USD wasn't too far off. Maybe a little higher or a little lower, but something so far away from nilenso's present reality need not be overly precise. It's just a helpful stake in the ground. For us, a $500,000 salary represents Developer Level 10.0 -- someone who's about to retire and has turned the industry upside down over the course of their career.There's huge value in imagining the highest salary you will ever pay. We humans don't like to spend a lot of time pondering the end of our productive days. We like to spend time pondering the scary last chapter of our mortality even less. But these things are real. Everything real, everything fact-based, has to be laid bare in a completely transparent organization.

Our first pass was difficult, uncomfortable, and (of course) incorrect.

Fast forward one year to nilenso's 2015 review cycle, and it was apparent our 2014 curve didn't really fit. We'd made a few mistakes: high-end salaries (L4.x and L5.x) were too high, some jumps had been too big, the L1 salary band didn't fit on a smooth curve. (You can see this from the graph: the L1-L2 salary band has a steeper slope than L2-L3 and the inflection at L4-L5 is also obviously incorrect.) However, being completely honest about the data is only step #1. Step #2 is to be completely honest with _ourselves_: we'd made some mistakes in 2014 and we needed to correct them. We jiggled the L1 salary band a bit, some L2.x salaries didn't jump as much as expected, L4.x and L5.x salaries came way down.

Our second pass was difficult, uncomfortable, and (will likely be) incorrect.

...but it was a little less difficult, a little less uncomfortable, and (hopefully) a little less incorrect. The goal is not perfection. Next year, the benefit of hindsight will expose this year's mistakes and we can once again go through the mild discomfort of correcting them. And, with any luck, our second pass was enough of an improvement on our first that the mistakes will be smaller.

I've jumped ahead of myself a bit, here. The 2015 salary curve starts at about 7.5 lakh rupees ($12,000 USD) for Developer Level 0.0 and curves relatively smoothly up to 317 lakh rupees ($500,000 USD) for our realistic Developer Level 10.0. Everyone at nilenso is presently L1.x - L4.x, so don't get too excited about multi-crore salaries we might lavish you with. But how did we arrive at the curve?

Reviews in 2015: Tim & Deepa to the rescue

Our review process in our first year wasn't too bad. Everyone received meaningful feedback and was given a clear path for growth. However, it felt ad-hoc, everyone's feedback/reviews were delayed (as they are in most companies), and it felt strange to have the Executive drive the conversation -- even the most logical and robotic Executives are still human and will introduce their own bias. In 2015, we improved on this thanks to two distinct efforts from Tim and Deepa, who signed up to organize the 2015 review process. This would normally be a thankless job, consisting mostly of manually coordinating an Excel spreadsheet. But not this year.First, Tim (being Tim) spent a Saturday automating the review workflow. The nilenso reviews app was born. Since any annual review cycle for any company tends to be little more than swimlanes of todo lists, it was the perfect job for Rails and Heroku. Tim, and anyone else at nilenso, could modify the workflow, relationships, and privacy across the reviews process in a matter of minutes with a quick code change and redeploy. Everyone could glance at https://reviews.nilenso.com to see their feedback and to hassle people who hadn't reviewed their colleagues yet.

The review app lets everyone ask for reviews/feedback from specific people. Reviewers are then tasked with completing a review for everyone who asked them. Each review is a free-form text entry field and a "suggested level" field, if the reviewer is comfortable suggesting the reviewee's growth in the past year. Though we'd initially planned on discussing salaries directly, the Level system addresses skill, contribution, network, and experience rather than what anyone "feels" other employees should make. This has the immeasurable advantage of keeping emotion out of the equation and keeping everyone focused on the facts at hand.

Second, Deepa facilitated the review meetings. After scheduling and planning each meeting with Tim, she played the role of non-participating facilitator to discussions which included the reviewee, everyone who gave them a review in the app, and anyone else who wanted to listen in. Each meeting started with everyone in the room grabbing a laptop (or iPad) and quickly re-reading the reviews in question, to make sure they hadn't missed anything. Then the reviewee would summarize their self-review and the reviews they'd received from their coworkers; we did away with "sponsors" and let the person speak for themselves. At the end of the summary, s/he would explain whether the average Suggested Level (calculated by the app) seemed appropriate. The floor was then open to discuss and debate. By the end of these meetings, everyone knew what everyone else's level would be for the upcoming year.

The meetings cost us a lot of time but everyone agreed it was time well spent. Attempts to limit participation in 2014 hadn't prevented the review meetings from cutting into everyone's work day, and in 2015 there was no question that the open forum felt totally transparent.

A good rule of thumb for corporate transparency: You're probably doing it right when everyone finds the transparency boring.

A small consulting company has a fixed amount of money to spend on annual raises. By working through the entire review process without discussing money, we were free to be completely honest with one another with feedback^ and conversation. Certainly some conversations were harder than others but the overall process was smooth. Once everyone's reviews were complete, Deepa took away a Level Curve (really more of a straight line with dots on it, like above) which she could retrofit our earnings onto. That became the proposed Salary Curve, which we discussed one last time and then finalized.

^ It's worth noting that we expect feedback to be a continuous, daily process. If someone is giving you new constructive criticism for the first time only in the annual review process, they've failed you miserably. Since peer-to-peer reviews take the form of "feedback" the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. Though we may muddle terminology, we try not to muddle intent.

Unsolved Problems

Though we have a smooth, meaningful Level/Salary Curve for developers, we are yet to figure out what this will look like for administrators, executives, project managers, designers, accountants, or operations staff. We only have one desiger, executive, and PM on-staff at the moment, so our best approach is to find some middle ground between industry averages and the developer curve. But that's vague. These roles are definitely in beta at nilenso.A meaningful salary curve for operations staff is even murkier. Though we have 3 people who do operations (security & operations, cleaning, operations & basic accounting) and their salaries are similar, the industry average for these positions is unfairly low in India. We're also less sure what the growth path for each of these folks will be in the coming 2 or 3 years. Mintu will certainly get bored of working security at some point, and we need to make sure the Salary/Level Curve for Operations makes sense in light of that.

Though nilenso has a very liberal paid leaves policy (unlimited sick leave and plenty of vacation), we do not have sabbaticals (unpaid leave) figured out. Sabbaticals present a number of difficulties: Does a senior employee have more access to sabbaticals than a junior employee? Someone senior undoubtedly makes more money and has longer vacations in any company, but most companies don't offer sabbaticals. Is one's salary based on a 12-month working year, or 12 months less any sabbatical months? How can we plan sabbaticals far enough in advance that they're comfortable for both us and our clients? How many sabbaticals can a consulting firm support in one year? At one time?

Nilenso has expenses. An office, non-billable staff, food, travel, books/classes/conferences, and a couple of internet connections. While everyone would love to take a sabbatical whenever they like, it is damaging to a company if the company isn't 100% remote and overhead-free.

Other Approaches

Discussing salaries-in-a-coop always leads to the peripheral topics: performance reviews, bonuses, reinvestment, paycheques, and sabbaticals. I was excited to find that talking with Tom Hall and Hakan Raberg the conversation was almost entirely focused on sabbaticals. Juxt and MavenHive take a similar approach: you get paid for the hours you work. A company could take this idea to either extreme: either by hiring subcontractors rather than full-blown employees or by laying out basic salaries and adjusting them every month.Tom hasn't chosen a model yet, and I'm guessing it will evolve with his co-op. His key issue is the ability for employees to take sabbaticals (he describes the need for sabbaticals as a "founding principle"), which for a consultancy implies salaries will swell and shrink with billable hours. At nilenso, we've had varying success with mixing hourly billing rates and monthly retainers. Depending on one's billing model, the process of taking sabbaticals could shift. Once Tom's co-op Gets Huge(tm), it will require operations, admin, and accounting staff. Those folks still need to get paid even if all the developers are off at HillHacks for a month, so I'm excited to see what solution he and his team opt for.

tl;dr

For us, decoupling performance reviews from both feedback and salaries has worked really well. Feedback should be a daily occurrence, not a yearly ceremony. Salary structure should be a consequence of financial planning, not individual evaluation. Because we were discussing "levels", rather than salaries, emotions were (largely) kept at bay and we could discuss facts. We will definitely use Tim's Review App again next year since we found it a great tool for getting things done and for discussions. We recommend you try it too!We will keep publishing our experiments, failures, and learnings. And we'd love to hear from you at hello@nilenso.com if you have a suggestion!

Huge thanks to Tim and Deepa for making this post happen!